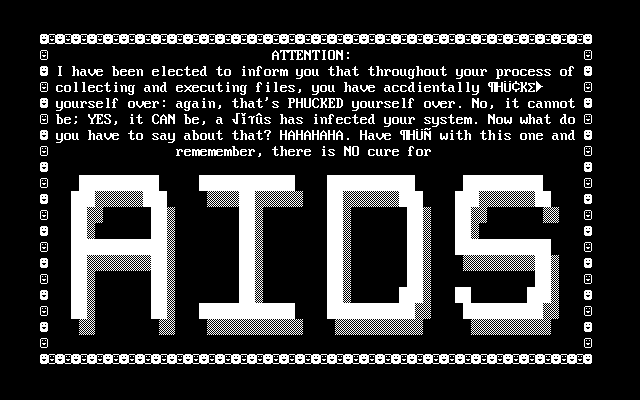

Ransomware is not new, as was covered in a previous post. Over the past two months, the Internet has been overrun by two malware variants which are responsible for destroying an immense amount of data and crippling corporations. In this post, we will use the concepts of access and authorization discussed in Think Like a Hacker to analyze its operation and better understand its propagation.

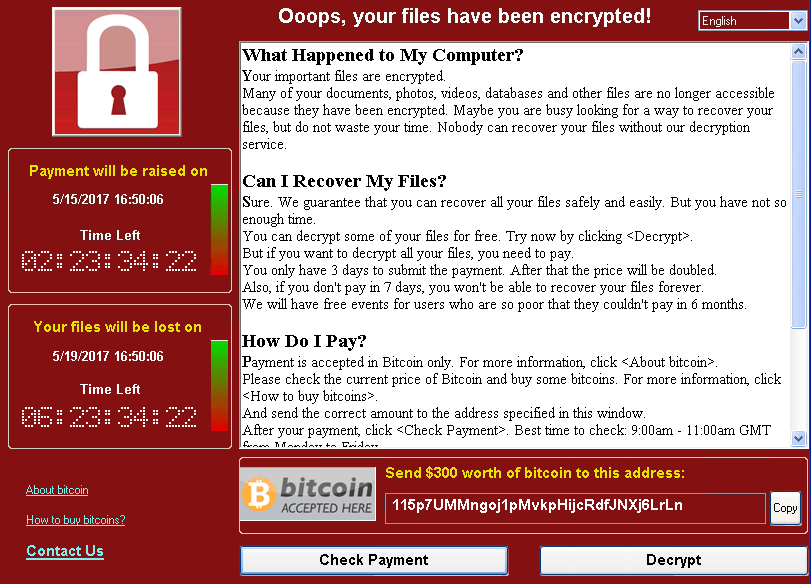

The Internet was introduced to a new type of ransomware on May 12, 2017 – one that leveraged an effective self-replicating (a.k.a. worm) capability to infect a large number of systems in a short amount of time.

Propagation of WannaCrypt was successful primarily due to its use of a powerful remote code execution vulnerability dubbed EternalBlue. Although novel, the implementation of EternalBlue in WannaCrypt was more of a copy-and-paste approach to an already disclosed and patched vulnerability.

EternalBlue

On April 14, 2017, a series of exploits were published to the Internet by a group under the name ShadowBrokers. This group had previously published other batches of exploits; however, previous disclosures were not nearly as powerful as EternalBlue.

EternalBlue is a tool which exploits a vulnerability in the Microsoft Windows implementation of the SMB 1.0 protocol. SMB is used heavily by Windows systems in an enterprise setting to transfer data between systems. Additionally, many non-enterprise users utilize this protocol to transfer files between systems, such as file sharing. For more detailed technical information about the vulnerability exploited by EternalBlue, check out CVE-2017-0144.

EternalBlue is a remote code execution exploit, which means successful execution of the exploit would enable an attacker to run arbitrary code on its host. In the case of WannaCrypt, the arbitrary code was itself – thus enabling the worming behavior.

Access

The widespread use of SMB throughout both public and private networks provided the malware to access a very large number of potentially vulnerable systems. Once a machine became infected, any machine accessible to that infected host over SMB may become the next potential victim. This created a target rich environment when paired with the worm capability implemented in WannaCrypt.

Authorization

The vulnerability exploited by EternalBlue could be accomplished without credentials, thus making the authorization required to execute this vulnerability effectively anonymous. Once exploited, EternalBlue enabled the attacker to execute code using the effective authorization of the SMB server service, whose identity is the “SYSTEM” account. As such, any code executed in this context will likely be unrestricted.

Effective Access and Authorization by Proxy

WannaCrypt utilized this pattern to rapidly infect systems throughout the Internet, starting with a single vulnerable system, then infecting any unpatched hosts which it could access over TCP 445 (vulnerable machines are those that had not installed MS17-010).

When paired with the lack of authentication needed to execute the exploit, this provided a platform for a highly effective worm.

Petya \ NotPetya

Petya \ NotPetya

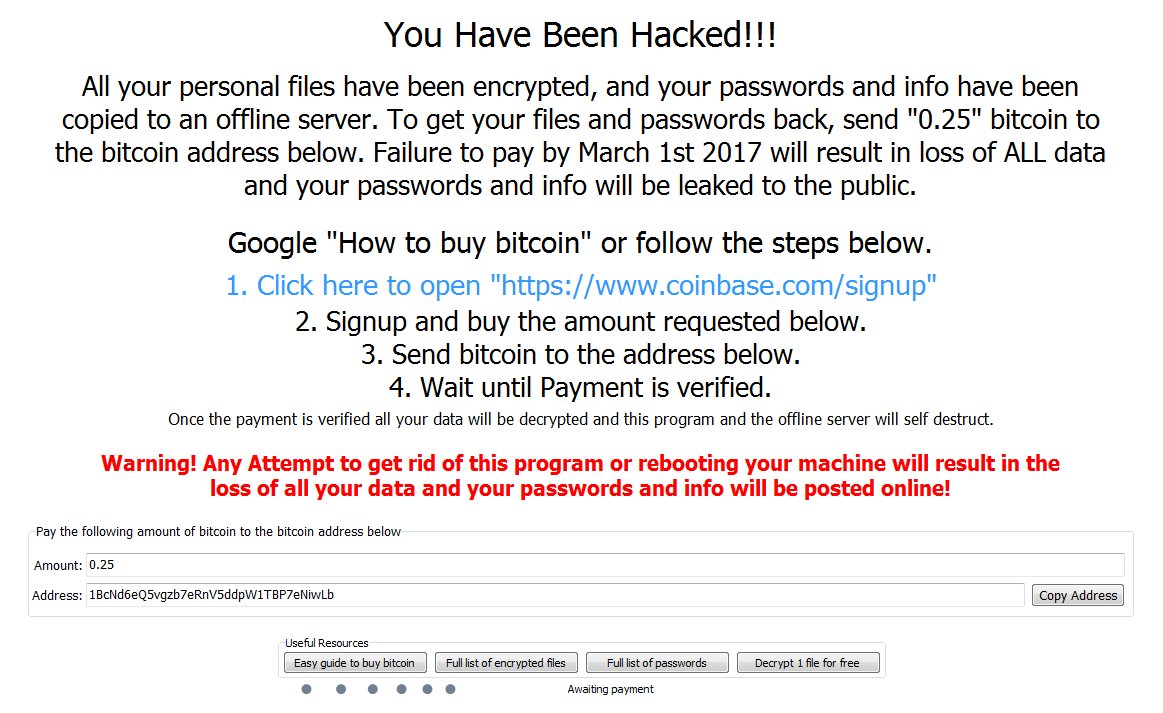

Just as the world was updating their systems to avoid WannaCrypt, another worm entered the picture – Petya. Like WannaCrypt, Petya leveraged EternalBlue to enable itself to propagate rapidly. Being on the heels of another worm utilizing EternalBlue means that fewer vulnerable systems will remain available for attack. Unfortunately, Petya didn’t stop at using EternalBlue.

Credential Theft

Petya was the “enterprise” version of WannaCrypt designed to take advantage of organizations with lax credential hygiene. According to the write-up by the Microsoft Malware Protection Center, Petya contained a tool with a large degree of similarity to Mimikatz, a tool commonly used for credential theft.

Use of pass the hash and credential theft as a form of self-propagation is rather new. Traditionally, tools of this type are run manually by penetration testing teams in search of enterprise configurations where a single credential provides local administrative authority to multiple systems. Petya marks the first documented time this technique was utilized to provide worm behavior at scale.

Petya’s use of credential theft tools shows a particular interest in attacking enterprise networks, as these tools are much more effective in environments where single sign-on or shared local administrator credentials are used. Additionally, Petya’s focus on accounts logged on using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) further demonstrates its interest in enterprises.

Successful use of credential theft enables the malware to masquerade as the stolen identity, thus providing authorization equivalent to logging on with that credential. In enterprises where every user has membership in the local “Administrators” group, a single stolen domain credential can provide local administrator authority to every workstation. If the stolen account has additional permissions beyond that of a workstation administrator (for example, a domain admin or member server admin), that instance of malware will gain the authority of that credential.

An infected machine will attempt to use these credentials to copy the Petya malware to the new victim machine and will attempt to start it using either PSExec or WMIC, both common administrative tools (the latter being a built-in Windows utility).

Access

Replication using EternalBlue is highly similar to WannaCrypt, therefore it doesn’t bear repeating.

When EternalBlue will not work, Petya will attempt to utilize credentials stolen through use of its credential theft tool to connect to potential targets over SMB. Therefore, in theory SMB must be available for Petya to propagate at all.

PSExec uses SMB to communicate with a target, which is presumably available if the malware is able to propagate in the first place. On the other hand, WMIC utilizes Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) which is implemented over Remote Procedure Call (RPC). This means that if the malware must use this means of propagation, an additional form of access must be available – access to both TCP port 135 (the RPC locator service) and whichever port the target is running WMI on (typically a random port between 1024 and 49152). WMIC was likely used as a work-around to accommodate for high security environments that block PSExec.

Authorization

If the target machine is not vulnerable to EternalBlue, Petya will attempt to use credentials stolen on its currently infected host to infect the new victim. To succeed, the stolen credential must have local administrative authorization (or equivalent) to the new infection target to enable copying of the Petya malware to the new target.

Unfortunately, many organizations provide administrative authority broadly within an enterprise to enable users to install their own software or to allow use of legacy applications. In addition, many organizations do not yet protect credentials of administrative accounts through credential hygiene or Credential Guard (a feature of Windows 10 and Windows Server 2016). As such, these enterprises remain vulnerable to credential theft and reuse attack.

Protection

Protection

Defense against malware such as the Petya worm requires security to be implemented in systems architecture, since software is only a part of the issue. Widespread use of accounts with local administrator authority can pose significant risk to an enterprise. Utilize techniques such as Service Centric Architecture to limit exposure of high value accounts. Additionally, Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) design can limit exposure to this class of attack by ensuring devices used by end users cannot expose credentials with administrative authorization to enterprise resources (i.e., non-domain member systems).

In addition, it is important to ensure machines throughout your enterprise remain at the latest patch level to avoid infection using recently discovered software exploitation techniques.

Last, always ensure your machine is running antimalware software with the latest definitions. Antimalware companies focus heavily on detecting and preventing self-propagating malware such as the WannaCrypt and Petya ransomware worms.