Determined human adversaries, or DHA for short, have changed the information security game for everyone. Many customers take actions in attempt to evict an emplaced attacker – actions that result in alerting the attacker to the organization’s knowledge of their presence, but don’t truly evict the attacker from the network. In this blog, we will discuss why a simple password change or implant cleanup does not impact a DHA – and provide insight into a comprehensive process for eliminating their presence.

The “H” in DHA is Human

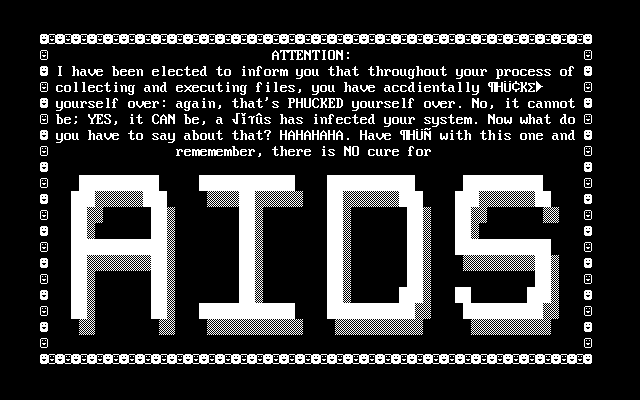

It sounds obvious, but it is easy to forget the human aspect of a DHA. Unlike normal malware infections (sometimes referred to as “commodity” malware), a human can identify and respond to changes in the target environment.

For example, a simple bitcoin mining application or botnet implant is one of likely thousands of hosts involved in the attacker’s scheme. In most cases, it doesn’t matter which machines commodity malware infects, rather it is about how many machines they infect. Removal of one, 10, or 100 nodes from a botnet dents the capability of the attacker, but does not significantly impact their operation.

In contrast, DHA implants typically have a specific interest in their targets. Typically, a DHA attacker will work to obtain access to a specific target. Once access is obtained, they will commonly setup multiple footholds within the enterprise to ensure that a single implant removal does not eliminate their access altogether.

Implants, Credentials, and You

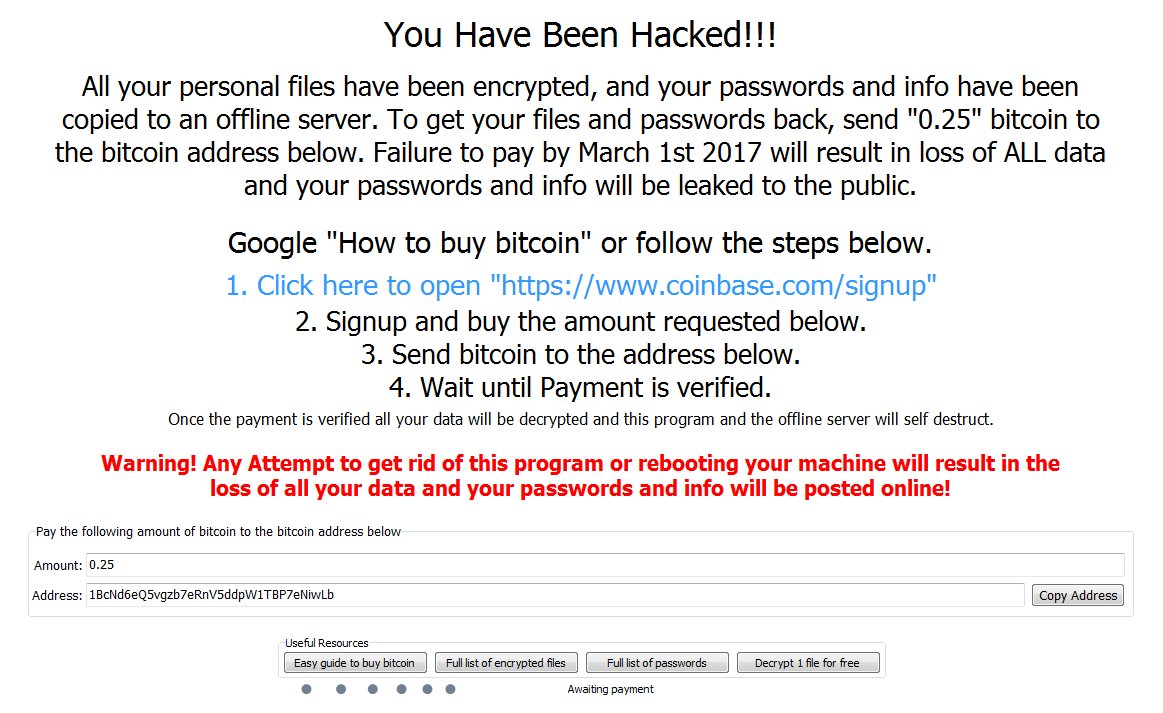

Malware implants are only part of the problem in a DHA infiltration. Once embedded, a DHA is likely to perform some sort of credential theft – either to elevate their current level of authorization, or to establish resilience in their forms of authorization. Resilience is key to a DHA and ensures continuing access and authorization to their target should their implants be discovered.

Credentials can provide durable access to a target, especially when paired with a powerful service, such as session virtualization (i.e. Remote Desktop Protocol) or remote management (RPC, WS-Man, SSH, etc.). With a sufficiently powerful credential, an attacker can re-establish access placing their target right back in the same situation they thought they remediated.

Tipping Your Hand

An attacker may change their persistence technique if they realize their existing implant has been discovered. Changes to command and control channels (the network path used by the attacker to communicate with the infected host), implant family, and other attributes surrounding the event may change, thus rendering prior research less useful.

Taking a Coordinated Approach

Responding to a DHA attack requires a coordinated strike addressing the ABC’s of the infection:

- Accounts (any identities known to be compromised by the attacker)

- Backdoors (the means that the attacker is communicating with “victim” endpoints, such as the malware implant or published management port)

- Command and Control (the network path used by the attacker to interface with the backdoor)

When planning to evict a DHA, ensure that your planning includes a concerted approach to eliminate as many of these aspects as possible as part of a single effort. Successful eviction will result in the attacker losing access and authorization to the enterprise, forcing them to attempt to establish a new entry point.

Bring in the Experts

When planning this activity, consider engaging consultants who specialize in remediating networks after a targeted attack. Consultants specializing in targeted attack perform this activity regularly and are typically more familiar with cleaning up targeted attack scenarios, thus their activities are less likely to cause unnecessary downtime and will be more aligned to disruption.